Pontine Infarction Presenting as a Syncopal Episode Associated with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome

Article information

Abstract

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement of primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is a controversial issue. We present a case of pontine infarction presenting as a syncopal episode associated with pSS. A 46-year-old woman was admitted to CHA Bundang Medical Center owing to right-sided weakness and dysarthria. She had no medical illness or smoking history but had a syncopal episode for the first time 3 days before. Eye and mouth dryness were found after history taking. Laboratory test results were positive for antinuclear antibodies: anti SS-A (Ro) and anti SS-B (La) antibodies. Diffusion-weighted imaging revealed high signal intensities in the left pons. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed multifocal stenoses of the basilar and bilateral vertebral arteries. Previous research on pSS mainly focused on peripheral nervous system manifestations. In our case, the associations of the CNS lesion of vasculitis with ischemia and pSS are considered pathophysiological mechanisms.

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (SS; pSS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by focal or confluent lymphocytic infiltrates in the exocrine glands such as the lachrymal and salivary glands, which are attributed to xerophthalmia and xerostomia. Alexander et al. 1 reported that neurological symptoms are observed in approximately 20% to 25% of SS cases. Neurological involvement associated with pSS is classified into two subsets: the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and central nervous system (CNS).

CNS involvement is a controversial issue, particularly in terms of its actual prevalence.1 PNS involvement is reported to be relatively high, occurring in approximately 10–20% of patients with pSS, but the incidence of CNS symptoms is a matter of discussion.2 Here, we present a case of pontine infarction presenting as a syncopal episode associated with pSS.

CASE REPORT

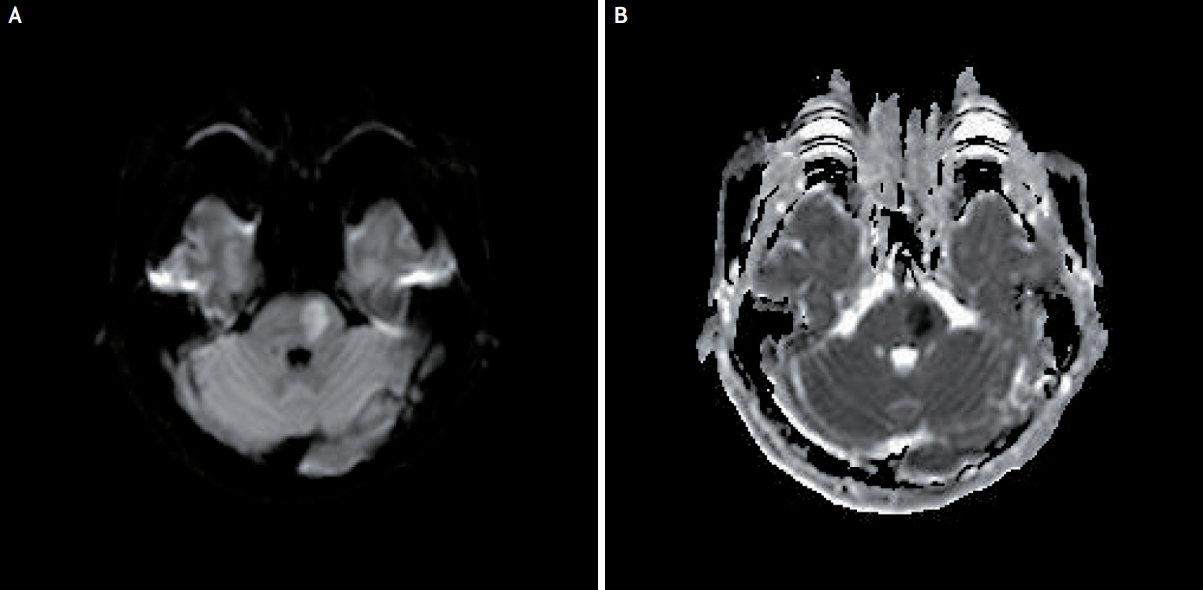

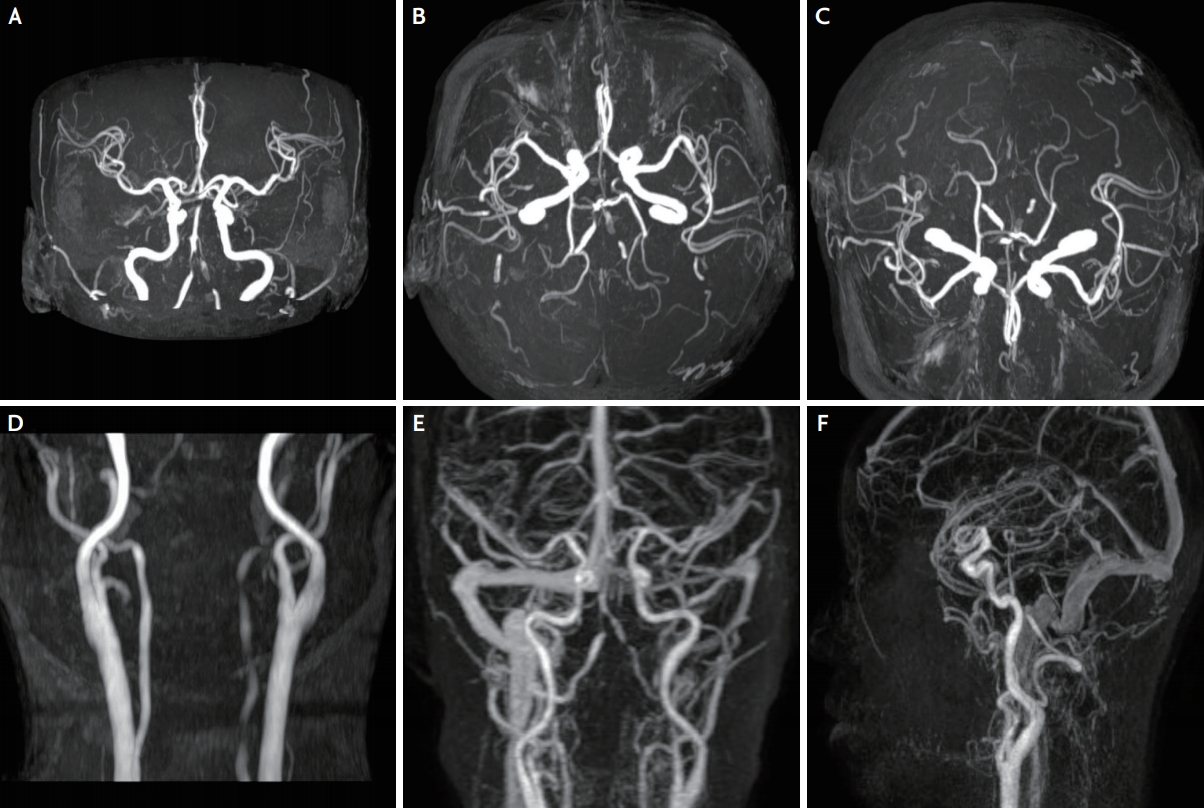

A 46-year-old woman was admitted to CHA Bundang Medical Center owing to sudden onset of right-sided weakness and dysarthria. She had no medical illness or smoking history but had a syncopal episode for the first time 3 days before. She had no sudden severe headache or trauma history. Before her hospital admission, she experienced a sudden onset of loss of consciousness for 10 seconds when standing up from a sitting position. Chest radiography revealed no acute pathology, and electrocardiography revealed a normal sinus rhythm. Her vital signs were stable, and her blood pressure was 140/78 mmHg. A neurological examination revealed right hemiparesis, right hemi-sensory disturbance, and right central facial palsy. Diffusion-weighted and apparent diffusion coefficient images showed high signal intensities in the left paramedian pons at the level of the middle cerebellar peduncle (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck revealed multifocal stenoses of the basilar and bilateral vertebral arteries (Fig. 2).

MRI of the brain. (A) DWI showing high signal intensities in the right paramedian pons. (B) ADC imaging showing low signal intensities in the corresponding area. MRI; magnetic resonance imaging, DWI; diffusion-weighted imaging, ADC; apparent diffusion coefficient.

MRA of the head and neck. (A-F) MRA image showing multifocal stenoses of the bilateral vertebral and basilar arteries. MRA; magnetic resonance angiography

Eye and mouth dryness were identified as significant findings after history taking. Laboratory test results were positive for antinuclear antibodies: anti-SSA (Ro), and anti-SSB (La) antibodies. The Schirmer test results were also positive. Lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin antibody, anti-smith antibody, anti-DNA, anti-Jo-1 antibody, anti-scl-70 antibody, anti-RNP antibody, anti-phospholipid antibody, rheumatoid factor, and ANCA were negative. The values of the other serological parameters, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level, were normal. In addition, no systemic signs of pSS, such as arthralgia, arthritis, peripheral neuropathy, and Raynaud’s phenomenon, were observed. The results of the brain electroencephalography, standard 24-hour Holter electrocardiography, and transthoracic echocardiography were all within the normal limits. In accordance with the 2012 American College of Rheumatology criteria, the patient was diagnosed as having pSS.3

Pulse methylprednisolone therapy was administered after the diagnosis of CNS involvement of pSS was established. Then, we used anticoagulation therapy and hydroxychloroquine at a daily dose of 100 mg. Three months after symptom onset, the patient remained stable without any progression of the initial symptoms, and her right-side weakness and dysarthria were partially improved.

DISCUSSION

pSS is a multisystem autoimmune disease characterized by hypofunction of the salivary and lacrimal glands. The main pathogenesis of the neurological involvement has been reported to be vasculopathy due to cryoglobulinemia and anti-SSA antibody, and ganglionopathy of the trigeminal nerve and dorsal root ganglia.4 The two processes appear to be partially involve autoantibodies, including anti-AQ4 antibody, anti-SSA antibody, antibody to acetylcholine antibody, antibody to small neuronal cells in dorsa root ganglion, and anti-M3-muscarinic receptor antibody.4,5

In real-life clinical practice, patients with pSS occasionally complain of pain in the extremities, such as dysesthesia, burning pain, arthralgia, and myalgia, and autonomic nervous symptoms such as vertigo, facial flushes, palpitation, hypohidrosis or hyperhidrosis, and diarrhea or constipation.4 Cerebral white matter and spinal cord lesions such as multiple sclerosis occur occasionally in pSS.6 CNS involvement with pSS is considered rare. The involvement of large arteries in pSS is also rare, as only a few cases have been reported in previous studies.4-9 However, the pathophysiological mechanisms of CNS involvement in pSS are still unclear. Many studies have suggested an ischemic mechanism.1,6,7 Acute focal symptoms could mimic stroke, which suggests the influence of an ischemic mechanism. A strong correlation was found between the presence of anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and vasculitis in patients with pSS.8 Therefore, anti SSA (Ro) antibodies are thought to mediate and strengthen inflammatory vasculopathy, which in turn can cause severe vascular narrowing. In addition, a case with positive anti-SSA (Ro) and anti-SSB (La) antibodies and cerebral vasculopathy associated with collateralization resembling the moyamoya phenomenon has been reported.9

Our patient did not have a history of venous or arterial embolism. We also could not find any possible cause of the venous or arterial embolism other than pSS. We think that the pontine infarction in our patient was the result of a vascular inflammation and stenosis related with the autoimmune mechanism of pSS. As a right but not a bilateral fetal-type posterior cerebral artery was found, it was thought to be due to stenosis, not hypoplasia of the basilar artery. In addition, the possibility of dissection was relatively low because vertebral artery stenosis was observed on both sides and the patient had no history of sudden head trauma or severe headache. The vertebrobasilar artery insufficiency in our case may be the recognized cause of syncope. After >6 months, the improvement of the stenosis on the follow-up MRA may be a more solid evidence of vasculitis, but follow-up angiography was not performed because of the patient’s circumstances. Moreover, we did not perform an imaging modality for histopathological confirmation and high-resolution magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging. Therefore, in this case, the possibility of stenosis of undetermined etiology due to insufficient association with vasculitis was not completely excluded. Other studies reported to date have not confirmed the definite association between pSS and stroke, but the findings are likely relevant because they are accompanied by other manifestations of pSS. As pSS-associated cerebral infarction requires urgent treatment, pSS must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with unexplained cerebral infarction.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.